Creature Feature: Abalone

The fastest snail in the west!

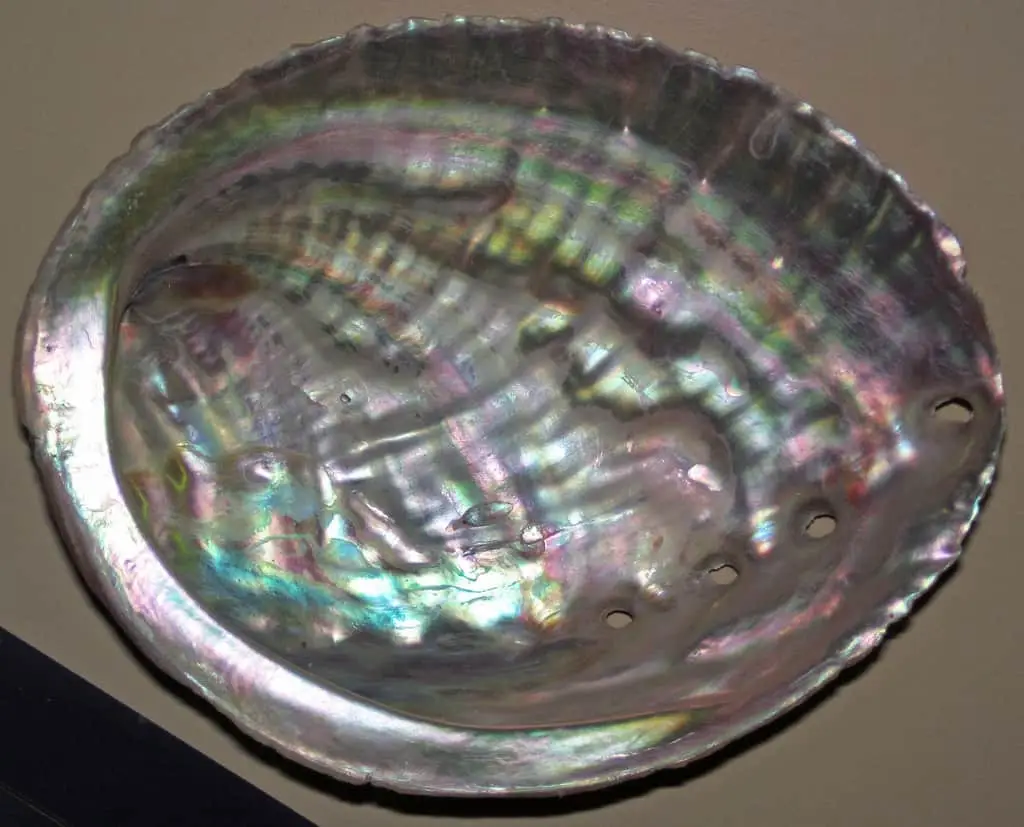

First Nations traditionally harvested northern abalone, or pinto abalone, on the BC Coast primarily for food and cultural use. The iridescent, mother-of-pearl shell was used for adorning blankets and regalia. If you are old enough, some of you may even know the taste of this endangered creature, considered a delicacy in many cultures. But you won’t find northern abalone on a BC menu today. The commercial fishery by SCUBA diving began on the BC Coast in the mid 20th century, starting very slowly and ramping up to reach its peak in the mid to late 1970s when Asian market demand brought up the price quite significantly. This demand, combined with the advancement of diving technology drove this commercial fishery to hit a high note.

The species was hit so heavily on the BC coast that the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) closed all commercial abalone harvest on the entire coast in 1990, including First Nations fisheries, due to serious conservation concerns. Abalone fisheries have been closed ever since. The species was then classified as Threatened and later upgraded to Endangered under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) in 2009 due to the lack of abalone recovery.

Interestingly enough, as salmon fisheries were declining, shellfish production ramped up as people began looking for other things to fish, and started looking at invertebrates such as abalone, urchins, sea cucumber, geoduck, and prawn. As a rather innocuous species, yet surprisingly fast moving, this well-camouflaged sea snail can easily be disregarded in the intertidal and sub-tidal ecosystems to the unassuming eye. However, they are a hot topic, particularly on the culinary black market for those who know of this endangered delicacy.

When the abalone fishery closed (and even when the commercial fishery was open), increased demand drove international market prices up. Illegal poaching was and continues to be a major threat to the species. Conservation efforts on the coast increased gradually with Fisheries Officer patrols and the addition of First Nations and other community-based Coast Watch monitoring programs opening more eyes on the water. Abalone poaching infractions can result in penalties of fines and even jail time, setting an example of severity for the offense.

In hopes to increase the population for culinary consumption, small aquaculture projects attempted to cultivate abalone on the east and west coasts of Vancouver Island in the early 2000s. Although an attempt was made to market some of the cultured abalone to high-end restaurants in Vancouver, the elaborate process of controlling chain of custody and the controversy that ensued made this difficult to continue. Abalone are often found amongst healthy kelp forest ecosystems – kelp being a food source on which they depend. These undersea forests also act as nurseries for a multitude of species in the nearshore zones. Sea otters, a keystone species, are a large contributor to keeping this ecosystem in balance.

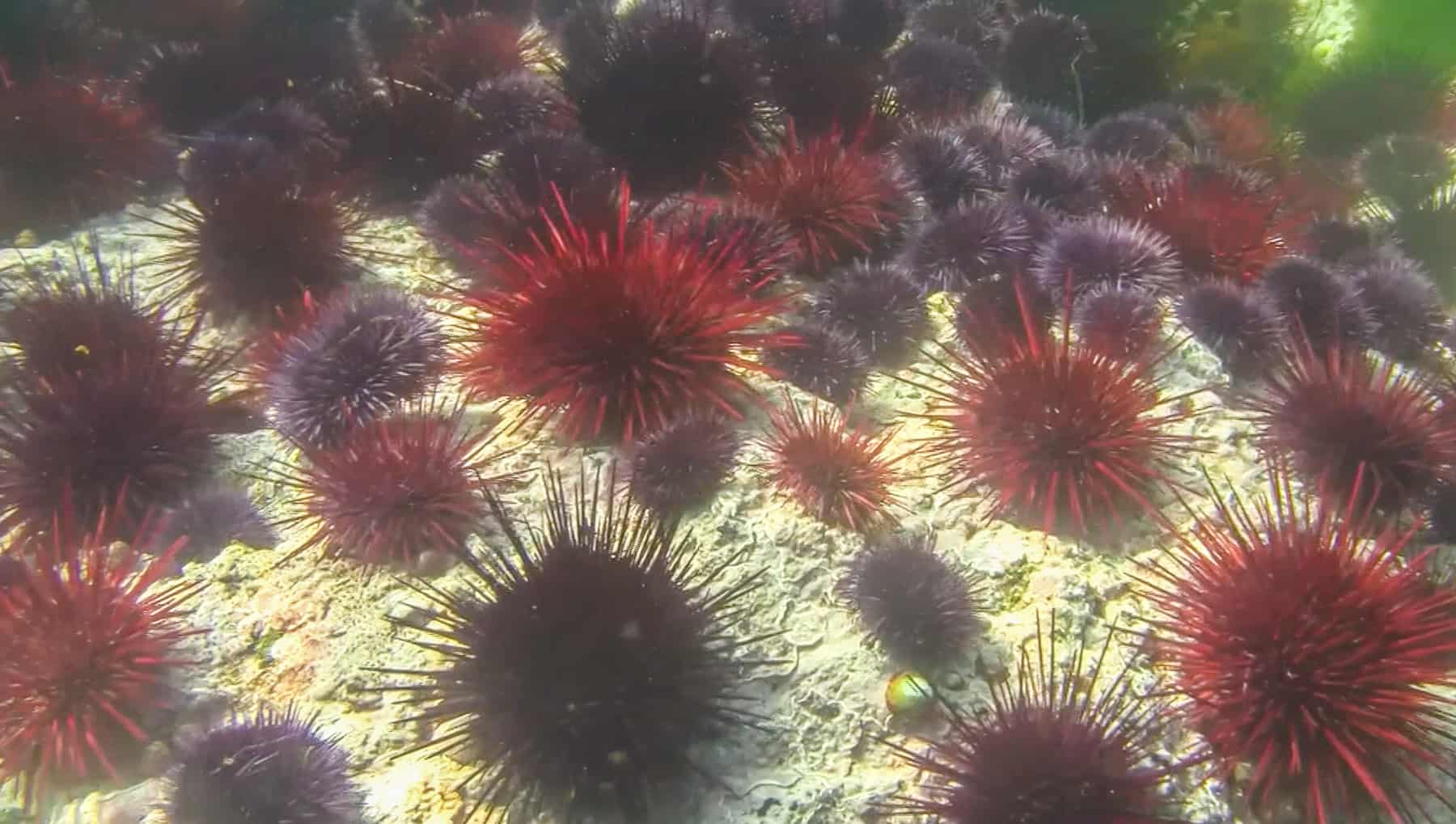

As a result of the fur trade in the late 18th century, sea otters were extirpated on the coast throwing off this balance. With the reintroduction of sea otters in some regions, it’s proving to help restore that balance, particularly with sea urchins (another favourite treat of this marine mammal). With the absence of sea otters over more than a century, urchins have devastated kelp forests creating barrens greatly reduced in biodiversity.

As sea otters also eat abalone, having them around reduces the population significantly. However, there are also benefits of having sea otters around because they also eat a lot of urchins. When there is nothing to prey on urchins, these voracious kelp consuming creatures devastate and mow down entire kelp forest ecosystems, destroying critical habitat for abalone – not to mention, a long list of other adverse effects for other species from rockfish, to seals, and even whales.

“In areas with sea otters, there was a large decline in abalone that were out in the open and a slight increase in abalone that were hiding in crevices, but also a great increase in kelp forest habitat for abalone and many other marine creatures,” says Lynn Lee, marine ecologist.

Today, researchers are discovering that in areas where sea otters have been reintroduced and kelp forests are returning, the distribution of abalone is being pushed downwards into deeper water. In fact, abalone densities are higher at deeper depths in areas with sea otters compared to areas without sea otters, and this is likely because the depth of the kelp forest is increasing and providing good habitat.

When sea otters eat urchins and greatly reduce their numbers, the kelp forests are able to thrive, providing a larger habitat and increasing the biodiversity. This, in turn, provides more variety of prey for sea otters and other species.

It’s difficult to determine how old abalone can get as it’s not quite the same as aging the rings of a clam, similar to counting tree rings, to determine age. As there wasn’t an accurate survey conducted before the fisheries began, it’s also difficult to determine pre-fisheries abundance.

Even after the closure in 1990, the population still declined. Apart from poaching, it’s hard to determine alternate factors that may have contributed to this decline. Other threats to the species include ocean acidification and climate change, and ocean conditions affecting larval production and recruitment rates, as well as the amount of kelp.

There has been an increase in abalone in BC in recent years, however, which could at least partially be attributed to the devastating Sea Star Wasting Disease that wiped out a large majority of sea stars on the BC coast. One of these sea stars, the sunflower star, is a major predator of abalone and loss of this sea star likely increased abalone survival rates.

DFO surveys now occur every 3 years to estimate species population, and 2019 marks the 10-year review for the species at risk classification for abalone. Lee is hopeful that abalone will be down-listed off the Endangered species list as the population has been increasing over the past 10 years, with significant increases in juveniles and smaller adults over the past 5 years.

“With a reclassification, this could open up doors to potentially allow First Nations access to once again harvest for cultural purposes,” she says. “We can then work with First Nations to consider management plans for their communities to sustainably harvest the species.”

Fragments of abalone shells have been discovered in midden sites along the coast, some dating back to over 2,500 years, although it’s quite probable that it extends much further.

“There’s a very interesting balance between people, sea otters, urchin, and abalone and how that was culturally and ecologically maintained in the past,” Lee informs me. “The loss of sea otters shifted the historical baseline and now that baseline is changing again as sea otters re-occupy the BC coast today.”

Hunting of otters goes back thousands of years and so does the harvesting of abalone. However, it’s only in the past 200 years, when over-fishing and over-hunting has caused massive species decline.

“Somehow people and otters and abalone figured out how to coexist for thousands of years in a way that didn’t destroy any of them. I think if otters were to repopulate the coast, we’ll have to figure out how that coexistence can happen again,” Lee hopes.