The Numbers Are In and the Final Report is Out!

It’s been a little over four months since the schooner Passing Cloud and crew returned from our Marine Debris Removal Initiative (MDRI) on BC’s Central Coast, and since then I spent a fair bit of time analyzing the data that our crews collected while in the field and writing up the Small Ship Tour Operators (SSTOA) and Wilderness Tourism Association’s (WTA) final report to the BC Government. Now that we’ve been through this process, I wanted to share with you an overview of what we accomplished and learned during this initiative.

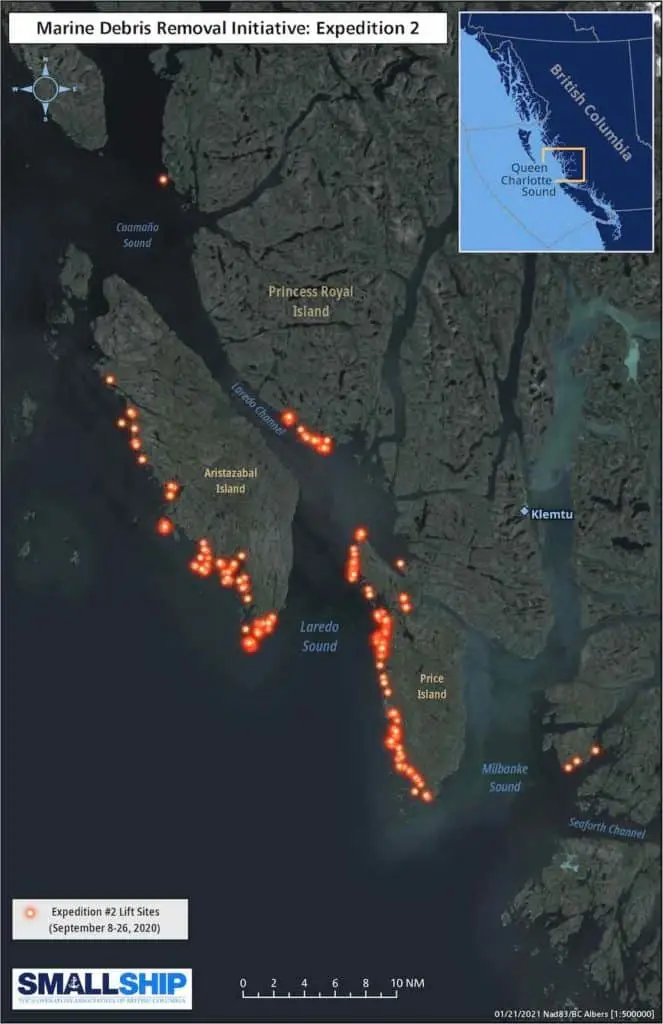

The SSTOA/WTA 2020 MDRI was funded by the Clean Coast, Clean Waters Initiative Fund (CCCW), part of the B.C. government’s Pandemic Response and Economic Recovery Initiative. This initiative included two 21-day expeditions, a fleet of 9 ships and 17 skiffs, and employed 111 SSTOA crew members and 69 First Nation community members. Collectively, we collected and removed 127,060 kg of beach-cast marine debris from 401 sites and 540.5 km of shoreline between Cape Calvert and northern Aristazabal Island, situated on BC’s Central Coast and Queen Charlotte Sound.

In terms of the outcomes of this work, it’s important to remember that the objectives of this initiative were both ecological and social/economic. Although difficult to quantify, we know that the removal of 127 tonnes of marine debris from our marine ecosystems, almost entirely plastics, will have substantial ecological benefits. Most notably, removal of this debris will reduce the risk of ingestion and entanglement by coastal wildlife, particularly seabirds and marine mammals, as well as reduce the production of secondary microplastics (see below).

The social and economic outcomes of the 2020 MDRI were also substantial, and much easier to measure. This project directly paid for 4,115 employment days, including 958 employment days for First Nation community members. And this funding indirectly supported an additional 5,405 employment days for SSTOA employees prior to and following the MDRI expeditions, paid for in kind by the participating SSTOA companies. Moreover, funding of this project will greatly help the ship-based tourism industry weather and recover from the financial storm caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and support the many communities and economies that depend upon the tourism sector in British Columbia.

An Education in Ocean Plastic Pollution

Because marine debris and ocean plastic pollution is such a vast topic, and new to many people, we dedicated Section 2 of the final report to providing an overview of some of the background, terminology, and environmental issues related to ocean plastic pollution and marine debris, as well as some sobering statistics. Most striking to me was the fact that, as of 2017, the global annual production of plastics exceeded 348 million metric tonnes (Mt), and an estimated 19-23 Mt/year is currently entering the world’s freshwater and marine ecosystems as macroscopic litter and microplastic particles.

The topic of microplastics is far too large to try to address here (see below for further resources), but the following definitions are important for making the link back to those 127 metric tonnes of plastics that our crews collected and removed. Microplastics are small plastic particles, fragments, or fibres in aquatic environments (freshwater and marine), and may be found floating at the surface, suspended in the water column, or settled on the seafloor. Microplastics are broadly produced in two ways.

Primary microplastics are purposely produced as the raw materials of industrial plastic manufacturers that use to build larger plastic items and are accidentally released into the environment during production and transportation. For example, nurdles and microbeads. The term microfibre refers to synthetic polymers, such as polyester, acrylic, and nylon that are used in spinning textile fibres and manufacturing approximately 60% of clothing materials worldwide. Unfortunately, as clothes made from these synthetic materials are worn and washed, they slowly shed microscopic plastic fibres (microfibres) that eventually end up in the ocean (the good news is that inexpensive filters are available for your washing machine to capture microfibres, see resources below!).

By contrast, secondary microplastics originate from larger plastic items (i.e., marine debris) that have been introduced into aquatic environments and subsequently degraded into smaller pieces by the action of the sun, temperature variations, abrasion, waves, shorelines, and marine life. Herein lies one of the key values of coastal clean-up efforts aimed at the removal of beach-cast marine debris before it can be degraded into microplastics – the more plastic that can be removed from shorelines directly reduces the production of microplastics.

Composition and Sources of Marine Debris

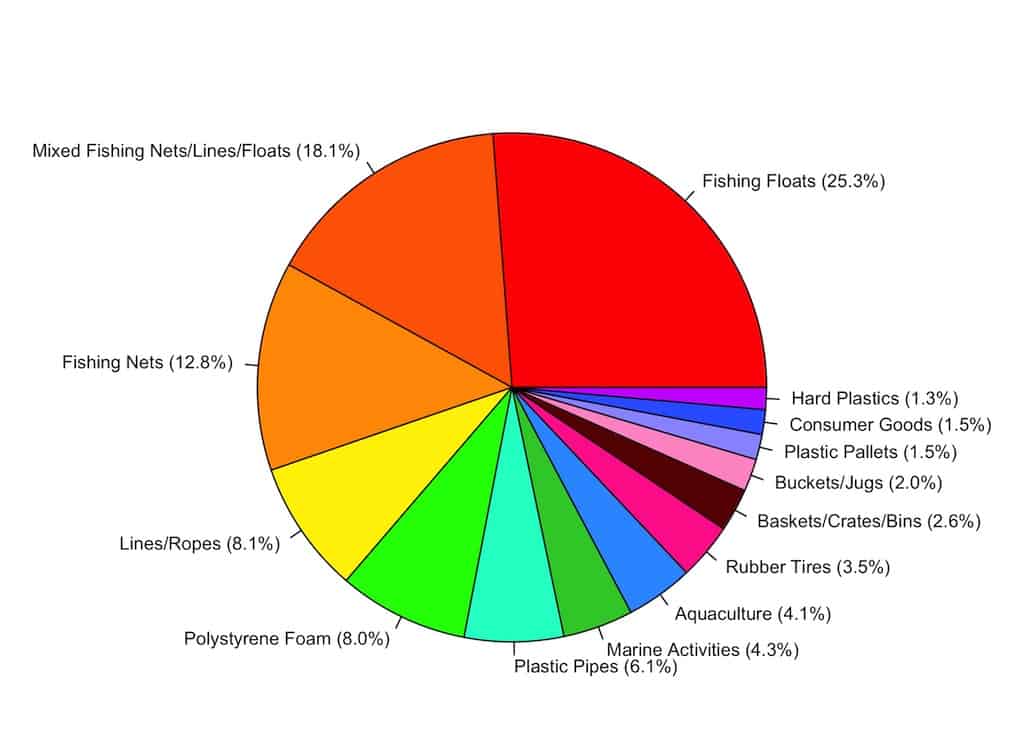

In addition to collecting and removing as much debris as we possibly could during this initiative, it was very important for us and the BC government to also document the composition of the debris we were collecting in order to inform and develop initiatives and policies aimed at halting the production of marine debris and ocean plastics. In our report, we describe in detail the methods we employed to collect this kind of information. What follows below is a pie chart showing the percentage of different types of materials, based on weight (kg), from a sample of 526 items with a total weight of 7571 kg.

What this figure shows is that 56.2% of this sample was composed of fishing floats, nets, and lines that were readily identifiable as fishing gear. This is the single most striking finding that has shocked everyone involved with this initiative. We have since learned that abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded commercial/industrial fishing gear is known a “ghost fishing gear”, and an estimated 6.4 million tons of fishing gear is lost in the world’s oceans, every year. As a result, ghost fishing gear constitutes a major component of ocean plastic pollution. Tragically, because this gear is constructed of plastic fibers, it persists in marine environments where it can entangle and kill marine wildlife for decades.

Although not shown in the figure above because a different sampling method was used, we also collected tonnes (literally) of plastic beverage bottles (mostly water bottles) that we found at nearly every location we visited. You may be surprised to learn (I was!) that around the world, an estimated 480 billion plastic beverage bottles are produced each year; one million are purchased each minute, and 20,000 are produced every second (see reference below). Unfortunately, vast numbers of plastic beverage bottles are not disposed of appropriately and find their way into the world’s oceans and to the most remote corners of the Planet, including the BC coast.

Finally, along with fishing gear and plastic beverage bottles, expanded polystyrene foam (i.e., StryrofoamTM), was also among the top three materials and items we encountered and collected during our two 21-day MDRI expeditions. Briefly, eroding expanded polystyrene foam is readily consumed by seabirds, fish, and marine mammals, resulting in blockages in their stomachs and intestines, and as such represents a substantial threat to coastal wildlife. On the BC coast, expanded polystyrene foam pollution originates primary from recreational and commercial marinas and floats, and commercial aquaculture operations, that use it for flotation.

I hope you’ll download and read the full final report, including our recommendations to the BC government, as well as explore some of the additional resources that I’ve included below. And please let me know if you have any questions, thanks!

Want to Learn More? Check out the final report and these additional resources

Clean Coast Clean Waters Initiative Fund

7 Ways to Reduce Ocean Plastic Pollution Today

5 Great Microfiber Filters to Help Stop Microplastic Pollution