FACES and PLACES: Sean Young, Haida Gwaii

The Haida are so intrinsically connected to the land, the sea, and the sky, and have been for millennia. The name “Haida Gwaii” aptly translates to “Islands of the People” in the Haida language. The Island archipelago is located roughly 100 kilometres from the British Columbia mainland. It is a place with ancient salmon-derived forests, skirted by white-sand beaches next to jagged limestone bluffs jutting out from the sea. Haida Gwaii is a place with an abundance of marine and terrestrial diversity, and a culturally-rich history interspersed amongst it all.

Getting to know the people of a place is so vital, particularly in this place where oral history runs so deep. You can read stories in a book, or look at artifacts in a museum, but there is nothing like sitting down with the locals who have been telling their oral history since time immemorial.

There is a saying in Haida:“Gina waadluxan gud kwaagid” which translates to “everything depends on everything else.” This saying speaks to the importance of community and the importance to work together to protect what you love because the Haida – and every Indigenous nation I’ve come across – believe you are not separate from this place, but rather one with it.

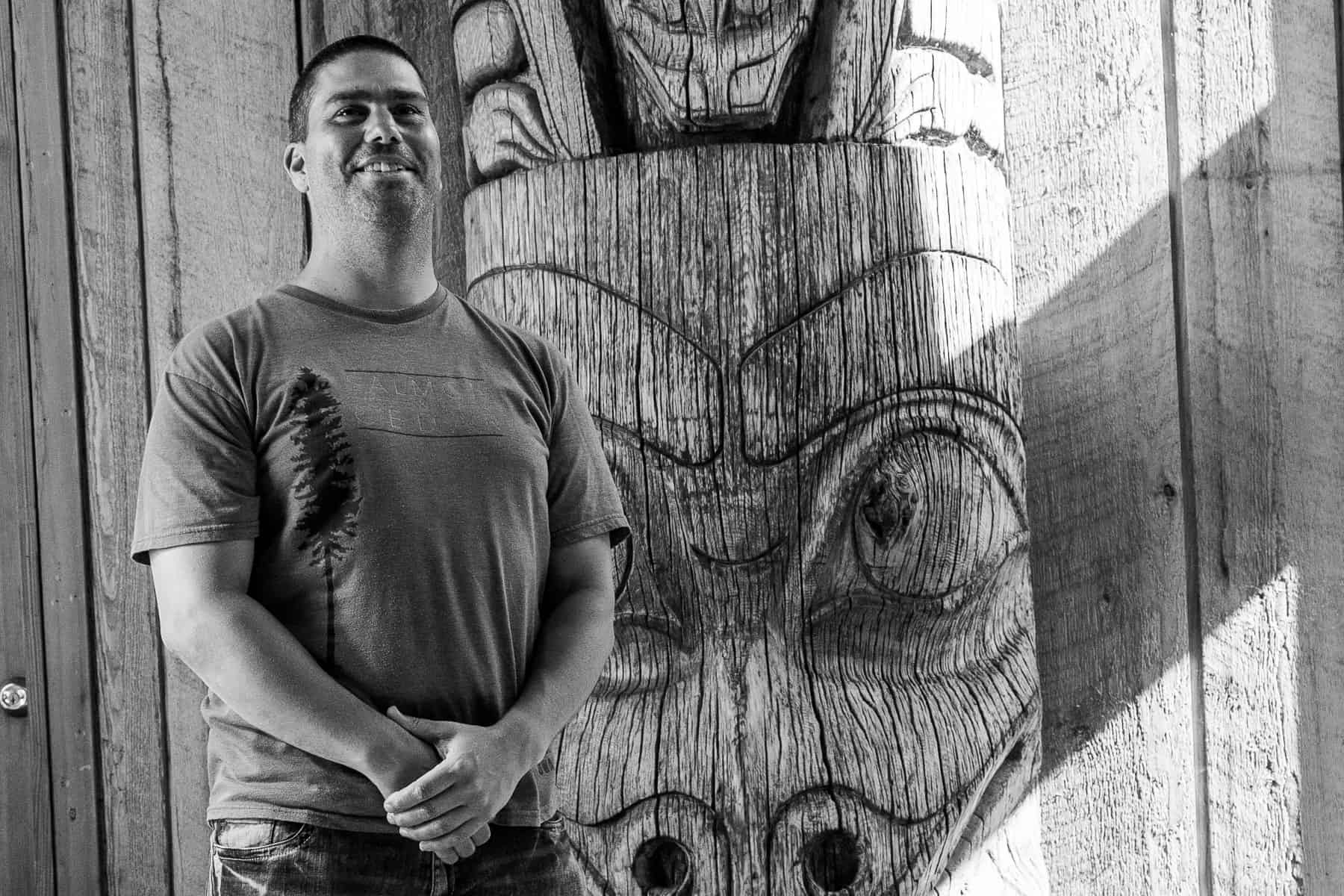

We couldn’t have asked for a better storyteller and cultural ambassador than Sean Young. Sean is an archaeologist and the Collections Curator for the Haida Gwaii Museum Society. He welcomes us to the museum on day-one of our Haida Gwaii expeditions for an immersive introduction to the cultural landscape.

Sean and his small team are responsible for the exhibits and collections at the Haida Gwaii Museum and he has been involved with many archaeological excavations and surveys throughout Haida Gwaii and Gwaii Haanas National Park Reserve. He is currently working on repatriating some artifacts back to the museum, which can be found all over the world from New York to London and beyond.

“There is actually more Haida art and artifacts in New York than all of British Columbia combined,” Sean tells us.

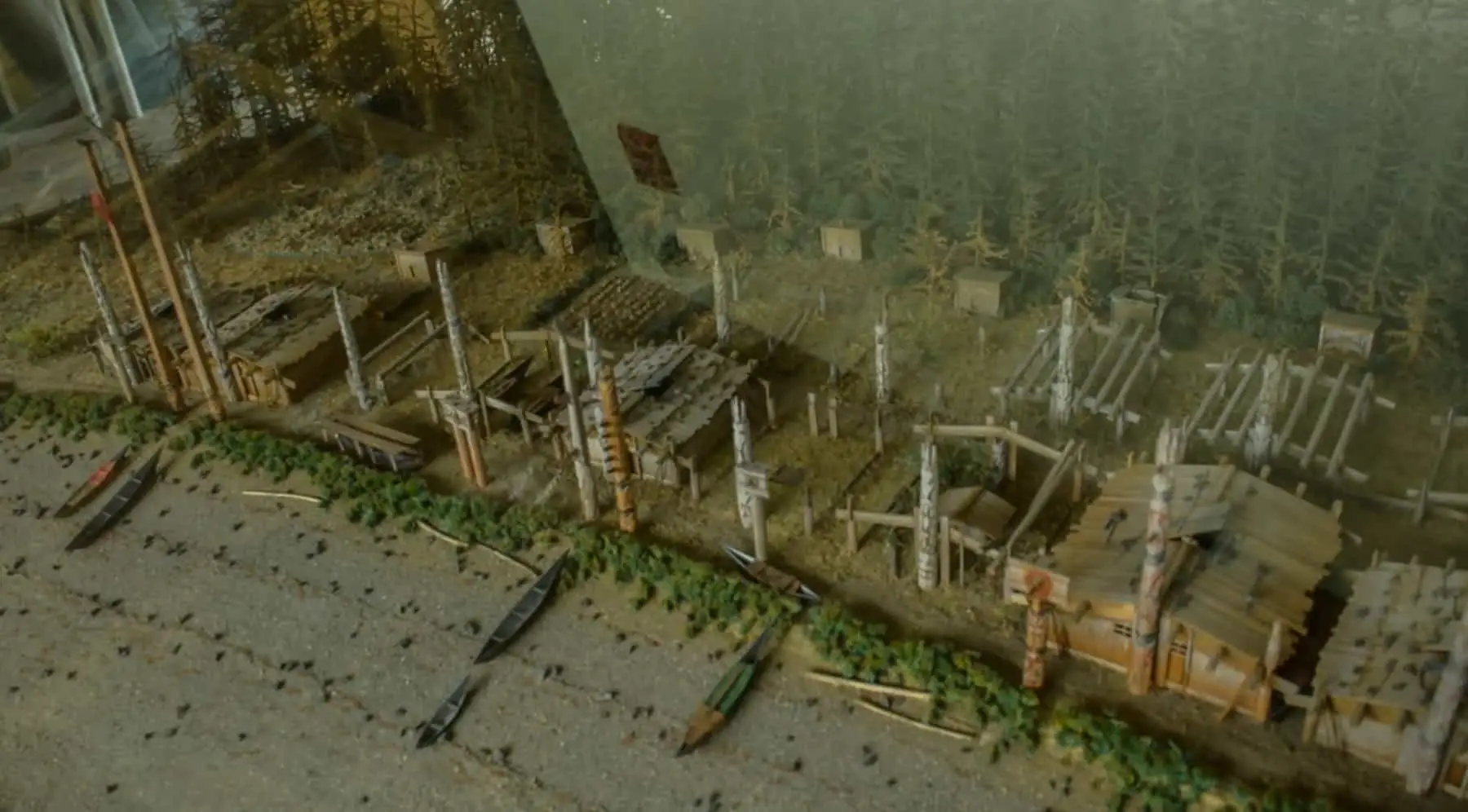

Museums around the world can help introduce and educate people about Haida society by exhibiting cultural objects from stone tools, masks, and mortuary poles, to whistles, rattles, baskets and even bones of animals that have long since been extinct or extirpated.

“There have been some really interesting finds that have come into the museum in recent history. A young lady found a petrified walrus skull in the North Beach area (Haida Gwaii) that dated to around 42,000 years ago.”

This skull is one of the pieces currently being repatriated from Vancouver’s Museum of Anthropology, along with a mask ‘Kalga Jaad’ or ‘Ice Woman’ carved by Reg Davidson which tells the story of the last glacial period. Unfortunately, oftentimes most of these objects subject to repatriation are sitting in a museum basement vault, outside of their traditional territory, or in another country and not even on display.

Sean walks us through the pre-contact section of the museum and not only shows us the artifacts but shares with us the stories passed down to him through his ancestors of the Gak’yaals Kiigawaay Raven Clan at K’uuna Llnagaay (Skedans). Sean points out a chest that was carved in the early 19th century that has been recently (and temporarily) repatriated on loan from the Museum of Natural History in New York for Guujaaw’s chieftainship potlatch last spring, naming him Chief Gidansta.

“It’s very significant and very intimate as it’s directly tied to my family because my great, great grandfather was high Chief Gidansta of K’uuna.”

The Haida have a very unique culture in the way they are able to match the physical archaeological evidence with oral history and cultural evidence. Our museum tour begins with the merging and linking of the science of archaeology, geology, and geography, complimented with Haida oral stories.

“They mesh and they tell the same story but in a different way. We always say they validate each other,” Sean tells us. “It’s quite interesting. The discoveries that we’ve found in recent years of archaeological work are actually directly linked to these oral history stories that we’ve had forever, and we’ve never known how old they really were until we dated all of the archaeological evidence. We found out two main stories that we have for origins of Haida culture and people. One is over 13,000 years old and the other is over 30,000 years old.”

The sea levels on Haida Gwaii have changed dramatically over the last 30,000 years. Present-day shorelines are roughly 140 meters higher than they were 10-15,000 years ago. The weight of ice during the last glacial maximum caused the archipelago to rise and the shoreline to fall, forming an isostatic depression on the British Columbia mainland, followed by post-glacial rebound resulting in rising sea levels. Therefore, much of the archaeological evidence of early civilizations is presumed to be below the ocean. Most of the village site remains we see today are only a few hundred years old, with one site in particular (Kilgii Gwaay) dating back to 10,700 years ago with stone tools and fish weirs, and the oldest settlements (that we know of) dating over 13,700 years. The oral stories, however, date back much further.

“We’re very lucky that we have those oral history stories to talk about it, and when we do the physical archaeological work we’ll actually be able to put names to tie to certain families and clans – if we’re very lucky.”

Sean has also spent many summers as a Haida Watchmen at each of the village sites throughout Gwaii Haanas. Each site in varying states of decay, with some poles still standing, while others have fallen back to the earth and now covered in moss and salal.

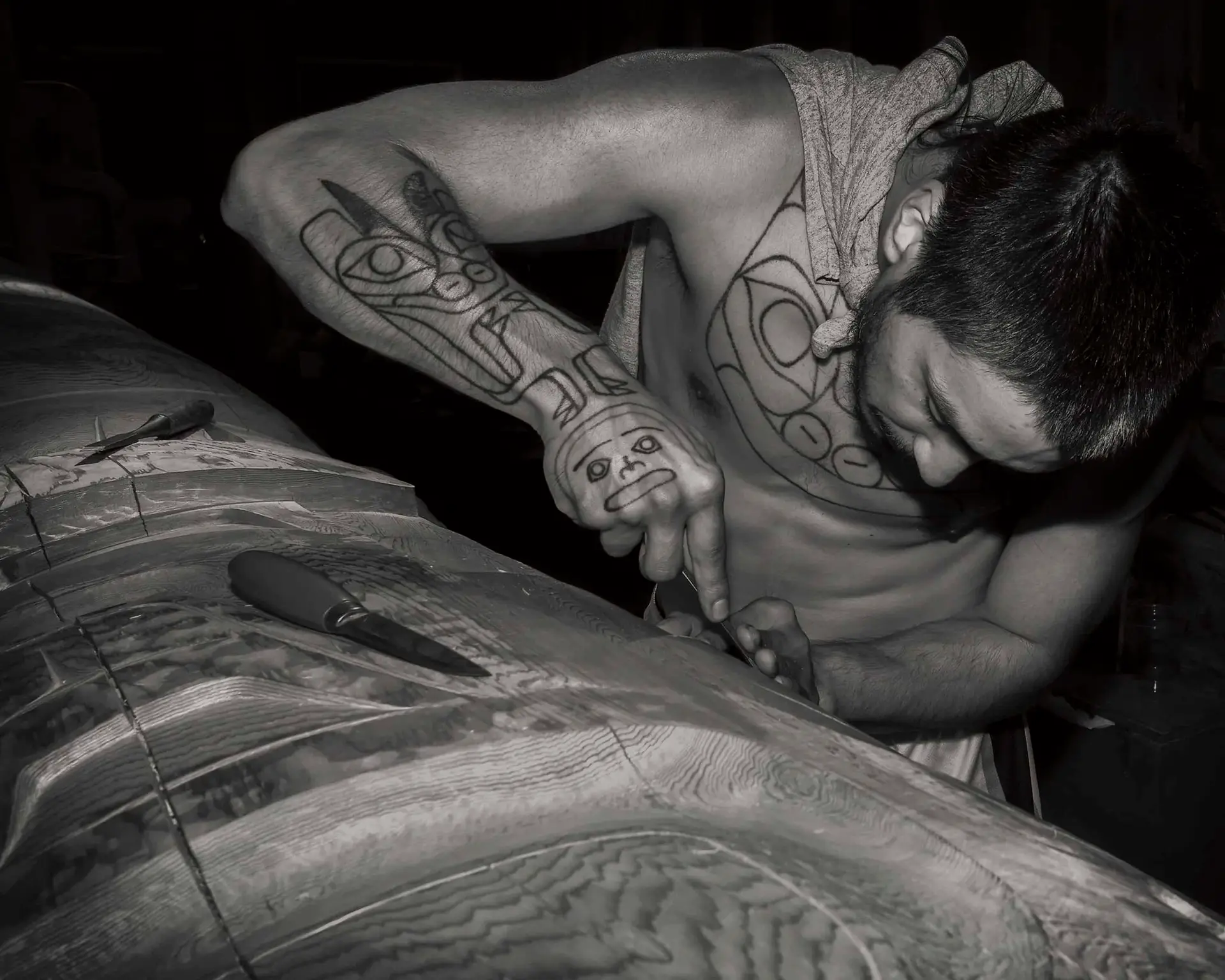

“Our culture believes ‘Once from the earth, back to the earth,'” Sean informs me.

The Watchmen Program started out by protecting the poles and house remains – including human remains of mortuary poles – when vandalism and theft was an issue. Today, the Watchmen still protect these sites and lookout over the land, sea, and sky, but they are also cultural ambassadors to educate visitors and carry on their history and ensure they are the ones to tell the story of their land. Many of the watchmen use this time and space to reconnect with their roots and their craftsmanship through carving, drawing, or weaving.

In his other role as a Watchmen and cultural interpreter, Sean is able to share his knowledge and experience to identify and explain to guests exactly what it is they’re looking at and put it into direct context. With so much information and history in the museum and at each of the village sites, it’s easy to get lost in the physicality of this place without knowing the full depth of the stories it holds. As visitors to this land, there are stories we will never hear, for they do not belong to us. We feel honoured to be a vessel, both literal and figurative, to connect our guests to the traditional knowledge holders whose home we are welcomed a window into for a short time, with hopes to bring a better understanding of people and place and the many complex issues that still arise today.

“The Museum is an important gateway to Gwaii Haanas and provides a baseline of knowledge on Haida Society and Culture, before entering the village sites themselves.”

We often find our guests are filled with questions about the Haida way of life, before, during, and after our time on board the Passing Cloud. Our time at the museum is a brief, yet important introduction before entering the ancient sites of Gwaii Haanas. Having the ability to match artifact to place and walk amongst these stories is very unique, and an incredible way to learn about this land and its people, directly from the source.

Sean sends us off with a message to go slow and be open to learning about this place from many different perspectives and reminds us that Haida is not a past culture, but rather a living culture, still thriving today.