By: Rebecca Martone and Maurice Kasprowsky

Once nearly erased by whaling, humpback whales have returned to the waters of British Columbia, reshaping a living seascape in numbers not seen for half a century

The first thing you notice is the sound, a thunderous exhale that vibrates through your chest. A fluke rises, glistening black and white in the sun, then slips beneath the waves. The majestic humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangilae) is surfacing again in B.C. waters.

Just a few decades ago, this scene would have been unthinkable. British Columbia’s coastal waters were once nearly devoid of humpbacks, their populations decimated by commercial whaling in the early twentieth century. Today, thanks to international protection and decades of conservation work, these giants became one of nature’s most remarkable comeback stories.

In British Columbia, humpback whales are recovering across the coast. In the Salish Sea, after decades of absence, the earliest modern sighting occurred in 1997, when a whale later nicknamed “Big Mama” was documented. Now a great-grandmother, she returned with another calf in 2025. Since then, more than 1,000 individual humpback whales have been identified in the Salish Sea and the Strait of Juan de Fuca, which is only a small portion of the BC Coast. [1, 2].

Outer Shores crew and guests are fortunate to be able to enjoy this rebound and to support the humpback recovery. We do this by contributing to the sightings databases that help researchers understand population fluctuations, while giving our guests the opportunity to enjoy and marvel at these gentle giants as they feed in B.C. coastal waters.

The Great Pacific Migration

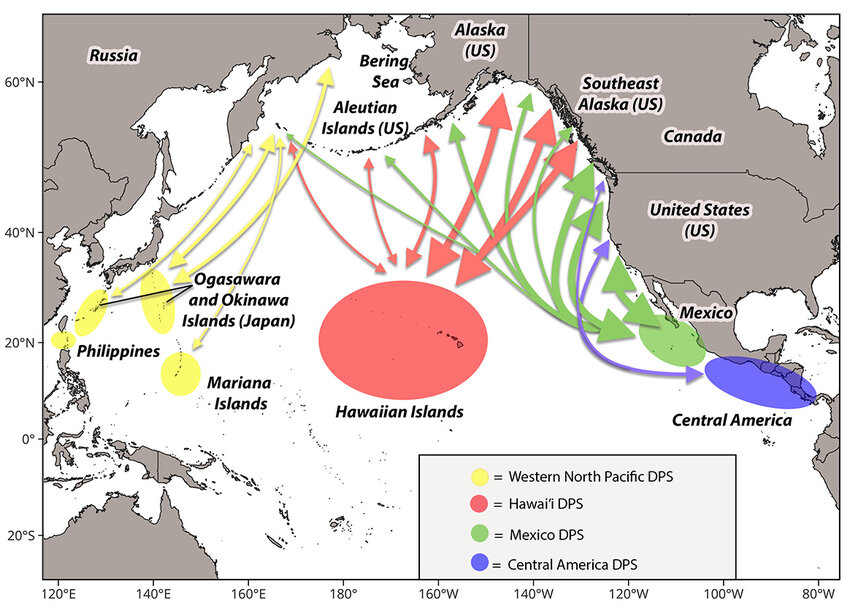

Humpback whales undertake extraordinary migrations across the Pacific, traveling thousands of kilometers between tropical wintering grounds and productive feeding areas in temperate and subarctic waters. The population in the Canadian Pacific is estimated at roughly 12,000 whales. Of these, about 64% migrate to Hawaii, 33% to Mexico, and a small minority to Central America [3].

This incredible journey, which can be as long as 6,000 kilometres each way, follows a pattern tied to seasonal productivity. During winter, humpbacks congregate in tropical waters, which are warm but relatively barren of food. Here, pregnant females give birth and males engage in elaborate courtship displays, including the species’ highly complex songs. In these shallow, warm waters calves can nurse and grow without the energy demands of the cold and with protection from predators found further north.

By late spring hunger drives the whales northward. The journey from Hawaii to British Columbia takes about one month. Satellite tracking has revealed that migrating whales maintain precise headings, moving steadily with little deviation. How they navigate with such precision remains unclear, but researchers propose several possibilities, including magnetic reception, cues from underwater soundscapes, celestial navigation, or even a combination of multiple tools. What we do know is that, compared with other migratory species, humpbacks appear exceptionally consistent in their routes, even across vast distances [4].

Where the Giants Gather: British Columbia’s Feeding Grounds

Humpbacks eat little to nothing during migration or while in their breeding grounds. For up to six months, they survive on the energy stored in their thick layers of blubber. This remarkable fasting period underscores the importance of British Columbia’s coastal feeding zones: they are refuelling stations for entire populations of whales.

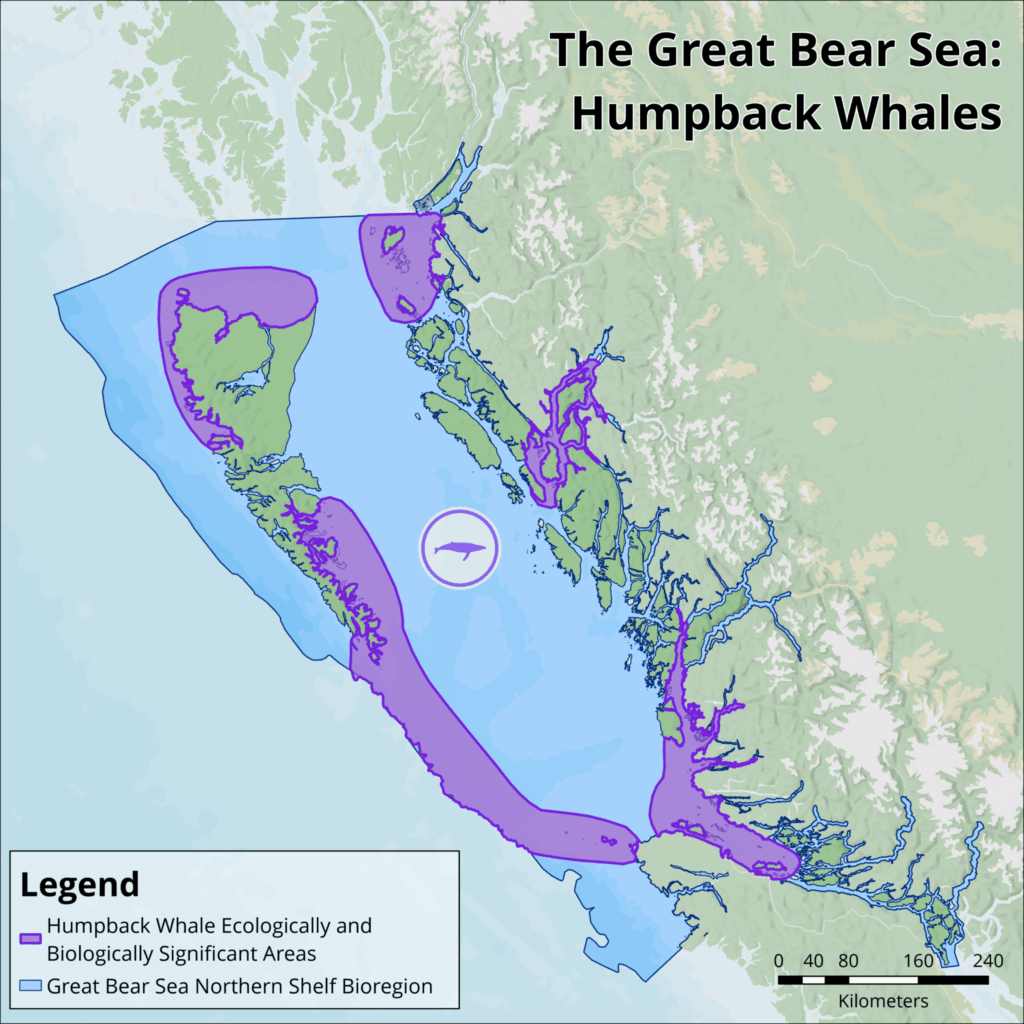

British Columbia’s coastal waters, a mosaic of fjords, islands, and deep straits, creates complex oceanographic conditions. Upwelling currents, tidal mixing, and nutrient inflows from the continental shelf create a buffet for the whales. These processes concentrate swarms of krill and schools of Pacific herring and sand lance, which form the whales’ primary diet, in predictable locations that the whales follow.

Many whales display remarkable site fidelity, returning to the exact fjords and feeding grounds where they were first weaned. Research shows that many individuals feed year after year in precise locations within the Fjord Systems of the Great Bear Rainforest, Haida Gwaii, the Salish Sea, and the Johnstone Strait [3, 5, 6]. These feeding grounds and the migratory routes are likely passed down generation after generation from mother to calf. Remarkably, calves complete this roundtrip just once with their mother and remember the route for life.

Feeding and Behaviour

For a species of such size, adults can reach 16 metres and weigh as much as 40 tonnes, humpbacks are astonishingly graceful. In British Columbia, they are frequently observed engaging in bubble-net feeding, a highly coordinated group behaviour, though some individuals also perform this behaviour on their own.

In this extraordinary feeding display, the whales dive beneath a school of fish, and release spirals of bubbles while swimming in circles. The rising column of bubbles corrals the fish into a tight baitball. Then, with perfect timing, the whales lunge upward through the center of the “net,” mouths open wide, engulfing their food along with thousands of litres of seawater, which they expel through their baleen plates.

Each whale in a feeding group appears to play a role — caller, net-maker, or diver — all of which are learned and socially transmitted behaviors [7]. During our encounters with humpback whales, we are fortunate to witness this group coordination and hear the complex feeding calls through our onboard hydrophone. Beyond bubble-net feeding, humpbacks employ a variety of other strategies, including trap feeding, where whales remain at the surface with open mouths and simply wait for fish seeking refuge to jump in [8]. This wide array of feeding techniques underscores the intelligence, adaptability, and sophisticated social behavior of humpback whales.

Songs Beneath the Surface

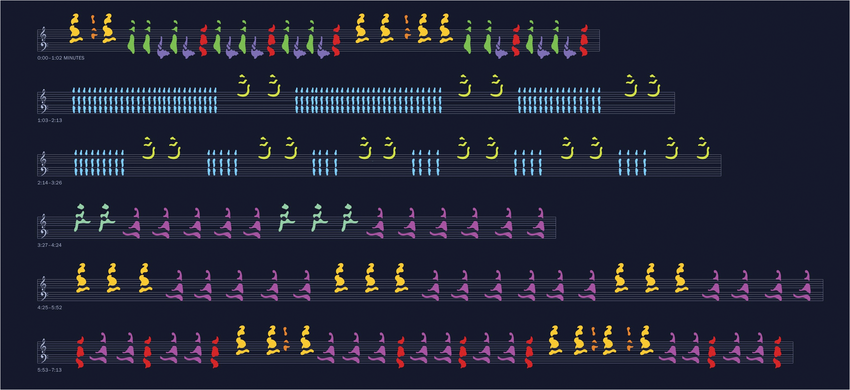

Perhaps the most enigmatic aspect of humpback whale biology is their song. When scientists analyze humpback vocalizations, they generally distinguish between two categories: song and non-song calls. Songs show a clear structure, with smaller repetitive units called phrases organized into larger themes that occur in a specific sequence, giving humpback whale song a kind of musicality reminiscent of hierarchical patterns in human music [9]. These compositions can last up to 30 minutes and may be repeated continuously for hours.

While all humpback whales can vocalize, only males sing. Songs are most commonly heard on breeding grounds, leading scientists to believe they play a role in courtship, though their full function remains unresolved. Decades of underwater recordings have revealed that males also sing on feeding grounds and during migration, suggesting that songs may be practiced or serve additional purposes, such as social communication [10].

Acoustic studies have revealed that within a breeding population, humpback whales all sing the same current rendition of a song. These renditions not only evolve gradually year to year but can also undergo dramatic shifts known as “song revolutions”. In such cases, an entirely new song type replaces the existing one across a whole population [11]. These changes have been documented spreading between breeding populations across vast ocean basins, a form of cultural transmission rarely seen outside humans [12]. The patterns and trajectory of these song changes suggest strong vocal connectivity among distant populations and highlight the whales’ capacity for rapid, socially learned cultural change.

Science of Identification

Every humpback whale has a unique pattern on the underside of its tail fluke, which researchers use much like a human fingerprint to identify individuals. In British Columbia, whales are catalogued using a naming system that reflects fluke coloration:

- BCX – mostly black flukes (< 20% white)

- BCY – mixed coloration (20 – 80% white)

- BCZ – predominantly white flukes (> 80% white)

The exact pattern of coloration, along with distinguishing features such as barnacle scars, divots, or unique fluke shapes, allows researchers to recognize individuals. Many whales have also received descriptive nicknames based on their markings: “Split Fluke” has a prominent cut through its fluke, “Lucky” bears many rake marks and misses part of her fluke from an orca attack, she was fortunate to survive, and “Mathematician” has markings that resemble mathematical symbols. The individuals are tracked in a centralized catalogue enabling scientists to monitor the population over time, including their movements, and overall population trends [1, 2, 3].

A Story of Decline, Recovery, and Continued Concern

A century ago, humpbacks were abundant in the North Pacific. Industrial whaling changed that. Between 1907 and 1965, commercial whalers killed an estimated 28,000 humpbacks in the North Pacific, driving the population to the brink of local extinction [3].

The international ban on commercial whaling, implemented in the mid-1960s, marked a turning point. Populations began to recover slowly, aided by national protection under Canada’s Species at Risk Act (SARA) [13] and the Marine Mammal Regulations of the Fisheries Act [14].

Today, the North Pacific humpback population is estimated at roughly 12,000 individuals. Annual growth rates of 4 – 8% (2004 – 2018) reflect a species steadily reclaiming its ecological role, though recovery remains fragile [3].

Despite this rebound, humpbacks remain listed as a species of Special Concern in Canada under SARA. Several ongoing threats continue to influence their rate of recovery:

- Vessel strikes: Humpbacks spend much of their time in coastal waters and along the continental shelf, where shipping and recreational traffic is heavy. They are the most commonly struck cetaceans in the Canadian Pacific [3]. In fall 2025 alone, three vessel strikes with humpback whales were reported in B.C., two of which were fatal [15]. Another example is “Moon,” a humpback whale with a severe spinal injury likely caused by a ship strike. Despite her paralyzed tail, she migrated from B.C. to Hawaii using only her pectoral fins but has not been seen since and likely succumbed to her injuries [16].

- Entanglement: Fishing gear and marine debris pose another serious risk. Whales can become ensnared, leading to exhaustion, injury, or drowning. A scar analysis study from 2022, revealed that upwards of 47% of humpback whales in Northern B.C. suffered from entanglement [17].

- Noise pollution: Noise can mask the vocalizations humpbacks rely on for communication, navigation, and coordination during mating, feeding, and migration. Increased noise reduces the effective range of whale calls, particularly affecting mothers and calves that depend on acoustic contact to stay together [18].

- Climate change: A major perceived threat is ecosystem change due to marine heatwaves, which are predicted to increase in frequency and intensity. Marine heatwaves alter prey availability, which can lead to increased mortality. During the “Blob” event in the North Pacific (2014–2018), food scarcity caused a 40% decline in humpback numbers in some feeding areas of Southeast Alaska, a warning of what may come farther south [3, 19].

Conservationists emphasize that mitigating these threats will be critical. Measures such as quieter vessels, dynamic shipping routes, and sustainable fisheries will play an important role in supporting the continued recovery of the humpback whale.

At Outer Shores, we hope to continue to support and witness the rebound of these remarkable marine mammals for generations to come, celebrating their return to the waters of British Columbia.

Resources:

[1] Happywhale. (2025). Happywhale.https://happywhale.com/home

[2] Tasli Shaw and Mark Malleson. (2024). Humpback Whales of the Salish Sea 2024.

[3] Government of Canada. (2022). COSEWIC assessment and status report on the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Canada. Environment and Climate Change Canada.

[4] Horton, T. W., Holdaway, R. N., Zerbini, A. N., Hauser, N. D., Garrigue, C., Andriolo, A., & Clapham, P. J. (2011). Straight as an arrow: Humpback whales swim constant course tracks during long‑distance migration. Biology Letters, 7(5), 674–679.

[5] Wray, J., Keen, E. and O’Mahony, É. N. (2021). Social survival: Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) use social structure to partition ecological niches within proposed critical habitat. PLOS ONE, 16(6), e0245409.

[6] Dalla Rosa L., Ford, J.K.B, Trites, A.W.(2012). Distribution and relative abundance of humpback whales in relation to environmental variables in coastal British Columbia and adjacent waters. Continental Shelf Research, 36, 89-104.

[7] Wiley, D., Ware, C., Bocconcelli, A., Friedlaender, A.S., Thompson, M., Weinrich, M. (2011). Underwater components of humpback whale bubble‑net feeding behaviour. Behaviour, 148(5), 575–602.

[8] McMillan, C.J., Towers, J.R., Hildering, J.M. (2019). The innovation and diffusion of “trap‑feeding,” a novel humpback whale foraging strategy. Marine Mammal Science, 35(3), 779-796.

[9] Payne, R. S. and McVay, S. (1971). Songs of humpback whales. Science, 173(3997), 585–597.

[10] Ryan, J.P., Cline, D.E., Joseph, J.E., Margolina, T., Santora, J.A., Kudela, R.M., et al. (2019). Humpback whale song occurrence reflects ecosystem variability in feeding and migratory habitat of the northeast Pacific. PLOS ONE, 14(10), e0222456.

[11] Allen, J.A., Garland, E.C., Dunlop, R.A., Noad, M.J. (2018). Cultural revolutions reduce complexity in the songs of humpback whales. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1891), 20182088.

[12] Schulze, J.N., Denkinger, J., Oña, J., Poole, M., Ellen C. (2022). Humpback whale song revolutions continue to spread from the central into the eastern South Pacific. Royal Society Open Science, 9(8), 220158.

[13] Species at Risk Act, S.C. 2002, c. 29. Government of Canada.

[14] Marine Mammal Regulations, Fisheries Act (1985, amended 2018). Government of Canada.

[15] Depner, W. (2025, November 13). DFO investigating 3rd whale death off B.C.’s coast within weeks. CBC News.

[16] North Coast Cetacean Society / BC Whales. (2023). Moon the Humpback Whale – tenacity and tragedy.

[17] BC Whales. (n.d.). Entanglement & ship strikes. https://bcwhales.org/entanglement‑ship‑strikes/

[18] Dunlop, R.A.. (2019). The effects of vessel noise on the communication network of humpback whales. Royal Society Open Science, 6(11), 190967.

[19] Neilson, J.L., Gabriele, C.M., Taylor-Thomas, L.F. (2017). Humpback whale monitoring in Glacier Bay and adjacent waters 2017 (Natural Resource Report NPS/GLBA/NRR‑2018/1660). National Park Service.